This article represents the opinions of its author. The views expressed here are not necessarily representative of The Sunrise News staff as a whole.

Fishing in Alabama is as synonymous with the state as football. Fishing for bass, catfish, brim, bluegill, crappie in Lay Lake or even saltwater fish in Mobile bay are all common pastimes in Alabama. Whether it be casual recreation or catching dinner, it’s a way of life for some people. For others though, fishing can be a personal challenge — an activity that can challenge both one’s ecological knowledge and technical skill.

Fly fishing is no exception. Why is it called fly fishing in the first place? What do you even catch? How does it work? These questions and then some are what I had when my friend, Grayson Curtis, spoke about it at work one day. He was patient with me and I saw his passion the more I spoke to him about it. Our other friend Robbie was there and he and Grayson started talking about making a video and shooting some photos of us. Eventually, my questions led me to holding a fly fishing rod and casting handmade lures for trout in the Sipsey Fork with a GoPro strapped to my chest.

I jumped a little too far ahead, though. Where I grew up fishing, and what is generally depicted in movies or pop culture, is known as bait casting. There’s tons of ways to fish, but I have always assumed that if my grandparents or friends asked me if I wanted to go fishing, there’d be a casting or spinning reel, some bait and a weight attached to the line. With what I knew of fly fishing, I always assumed it was the same setup and people who fly fished casted weirdly. I never thought about it past that and now know I was incredibly wrong.

Fly fishing still uses a rod and reel, but both are slightly different from a bait casting reel or a spinning reel. One of the main differences is the line — fly rods will have a fly line, a leader, a tippet and a fly.

Fly lines are typically bright orange or green and make up the majority of what’s in a reel. The leader and tippet are clear and attach to your fly line. The leader connects your tippet to the fly line and will start at a similar width to the fly line but tapers down to the tippet. The tippet is a light, clear line that ties to your fly.

The fly line is weighted and helps you cast your fly while the leader and tippet are attached to the end of the fly line to help direct the momentum of casting down the line — allowing better placement of your fly.

The other main difference between bait casting and fly fishing is your bait. Casting will use anything from live bait like worms or crickets to artificial spinnerbaits and jigs. By using a light line with a weight and heavier bait, the weight at the end of the line carries your cast.

Fly fishing can technically use live bait, but it’s not as effective. That’s why fly fishing mainly uses artificial bait made to look like types of insects or small fish and other critters, called flies. This bait is typically quite light and so the heavier line on your rod is what then carries your cast instead of the attachable weight.

Flies, like any bait, are dependent on what you’re fishing for, where you’re fishing and when you’re fishing. Most flies will imitate insects in the water and are generally one of four types of bait: nymphs or wet flies, emergers, dry flies and streamers. Each type of fly will imitate a different part of an insect’s life cycle or other fish food.

A nymph sits at the bottom of the water, imitating the early stage of an insect, an emerger sits just under the surface of the water, imitating the middle stage of an insect or other critter, and then an adult insect sitting on or near the surface of the water can be imitated by a dry fly. Streamers can also represent an insect’s life cycle stage but typically imitate larger bait like crawdads or smaller fish.

While you can imitate certain insects like a mayfly or a stonefly all day, if those insects aren’t hatching at the time of the year in your specific area, then the fish won’t bite. You can easily find what the fish might be eating either from looking it up online, going to a local fly shop and asking a local or just looking at and around the water.

For example, when we stopped at the fly shop, Riverside Fly Shop, five minutes away from where we fished, the man working at the time told us what the trout would be biting. So, Grayson bought some new flies to try out. When we got to the bank, we noticed the trout were mainly top-feeding, and, it was mayfly season, so we started off casting dry flies that mimicked mayflies.

Fly fishing is considered to be by many as not just another way to fish, but an art form. It takes a technical skill to cast the line, but without the right finesse, ecological awareness and creativity, that technical skill can be useless. I haven’t even mentioned the ridiculous skill and creative expertise it takes to create your own flies. There are an unlimited number of ways to craft and alter hooks, string, feathers, furs and other materials to imitate prey.

I’ve gone into some rambling detail about fly fishing, but what about fly fishing in Alabama? Well, there’s a reason I hadn’t really heard about it despite growing up with my brother going fishing at my Nanny’s stock pond in Perry County. It’s because it’s just not as common in Alabama, at least to the extent in places like Montana or Colorado.

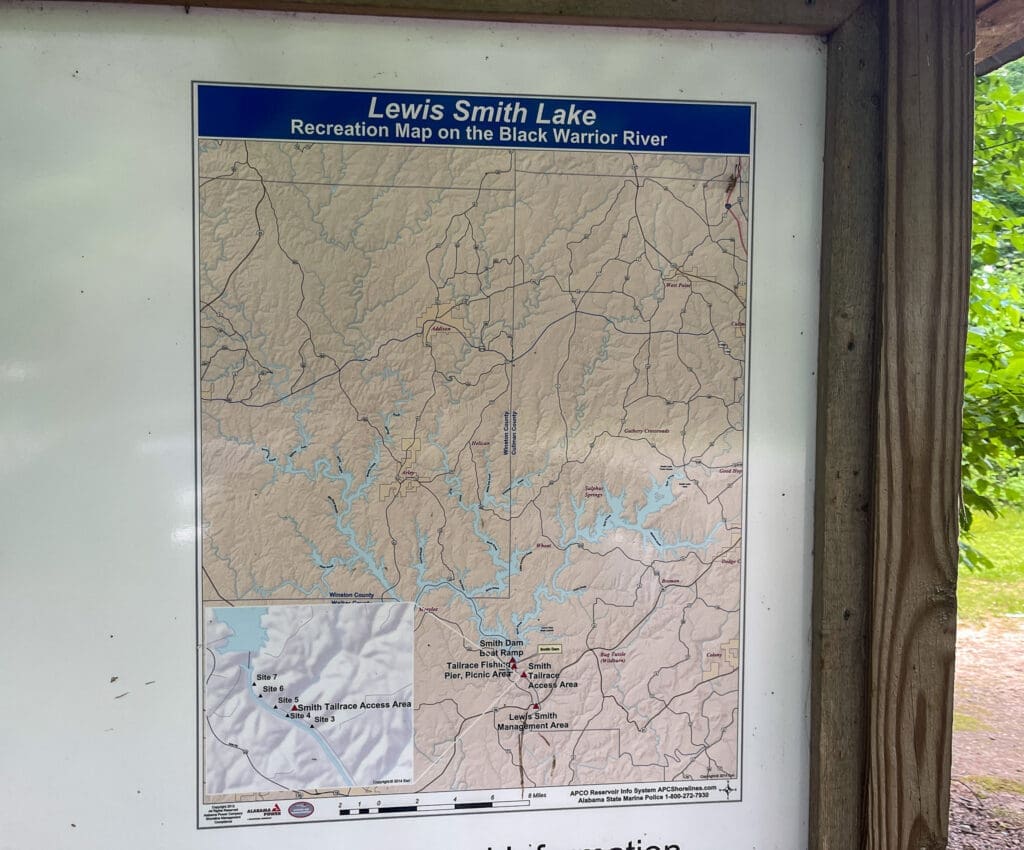

Technically, you can fly fish anytime of year for whatever fish you want. But, the gold standard fish, the fish most fly anglers seek out, is the rainbow trout. Trout, however, only thrive in water ranging from the 40s to the mid 60s. Cold water is hard to find in the Alabama heat. That’s why the only year-round place to go fishing for trout is at Sipsey Fork, under Lewis Smith Lake.

Since 1974, rainbow trout have been stocked at Sipsey Fork. The water is cold enough due to the dam pulling water from the bottom of Lewis Smith Lake, and stays cool enough for the 12.5 mile stretch of the Sipsey Fork until it runs into the Mulberry Fork. Typically, trout are stocked every third Thursday of each month but can change depending on weather conditions and water levels.

Minimum waters, the lowest amount of withdrawn water before there is environmental harm, are maintained along the Sipsey Fork by a collaboration between Alabama Power, the Alabama Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries Division (WFF) and the US Fish and Wildlife Service to better improve conditions for the trout and to better resemble natural habitats for the fish.

When we stopped by Riverside Fly Shop, there was an older man talking to the person running the shop. He had asked about the water level and falling waters. I was confused about what he was talking about, but Grayson later explained to me about the possibility of rising waters, but we didn’t need to worry because we would have enough warning before water levels rose, if they did. When electricity is being generated, water levels will rapidly rise between 12 to 15 feet high. So it’s important to be aware of scheduled generation by calling 1-800-LAKES-11; however, generation is on a demand basis so we were sure to listen for warning sirens.

I keep mentioning Riverside Fly Shop, but I haven’t explained what it is yet. This was our first stop on our trip. It’s on the Sipsey Fork and is about an hour and a half away from Columbiana. It looks like an old wooden cabin on the side of the road with a gravel parking lot. When we walked in, there were two older men having a conversation about fly fishing and how they’d been doing. Grayson, Robbie and I walked in and I was overwhelmed with the amount of fly fishing gear.

It would be a safe bet to say nearly every fly in that shop was handmade. In the center right of the shop was a fly making station and just past that was a room with every material you’d need to start making your own flies. Grayson bought a few flies and a hat while Robbie and I aimlessly looked around the brand new world we just entered.

The shop provides classes for fly tying, fly casting and rod building. They also have gear rentals, kayak rentals and guided trips. If you go to Sipsey Fork, I highly recommend stopping by, even if it’s just to look around.

Along the Sipsey Fork, there’s numerous accessways and ramps, but we drove along CR 95, across the street from Riverside Fly Shop, towards the dam and stopped at an access site to fish for about an hour. CR 95 is also labeled as the Smith Tailrace Access Area on the signs and maps along the road but doesn’t show up on Apple Maps or Google Maps.

Grayson showed me the basics of how to cast with a 9 ft 5 weight rod and started me off with a dry fly imitating a mayfly. He had a 9 ft 8 weight rod and used wooly buggers to imitate smaller fish. Eventually, he also switched to a mayfly dry fly and I tried using a gnat dry fly but ended up switching back to the mayfly.

My first few casts were awful. It was like learning to ride a bike again if the pedals and handlebars were swapped. It was just backwards to me, and I was forced to be more reliant on the feeling of the full rod and line rather than just blindly casting with a weight at the end.

I persisted though, I remained patient, watched Grayson and focused on the feeling of the cast and found that feeling.

After fishing the first spot and not seeing many fish at all, we drove to the end of CR 95 to the Sipsey River Intake Pump Station, or Blevins Hollow, which is right next to it. Both show up on Google Maps but neither show up on Apple Maps. We used Apple Maps, so we just followed CR 95 to a dead end until we saw the pump station.

Once we got to the pump station, instead of going towards the obvious access that is seen from the parking area, if you follow the fence — which do not touch, it is electric — you will eventually find a trail going into the woods. By walking another five minutes or so, you’ll find a much more secluded access point to fish at.

This area of the river is wide and open, with plenty of water to fish. We immediately spotted two or three great blue herons and knew there were going to be fish. Walking over to the water, we saw our assumptions were right. The area of the river we focused on goes from rolling streams to a small bend into deeper water that had tons of trout top-feeding.

Equipped with our Chacos and shorts, Grayson and I wet-waded, going in the water without proper waders, into the water to get some better casts and expected to start getting bites. At this point, after getting nothing, Grayson showed me a technique called dead drifting. You cast your dry fly upstream and let it float around the rocks in the water to imitate a dead fly drifting downstream. It felt like it was going to get a bite, it made sense, and the trout were eating whatever else that was drifting on the surface, but they just didn’t want my dry flies.

By now, I had become more confident in my cast so the fact that the fish weren’t biting made it that much more frustrating. After walking up and down the river, Grayson finally got a bite. I was roughly 25 yards upstream so I did my best to run down the loose rocks and shoals to get a good look of the rainbow trout. I was thrilled that we got at least one fish.

I went back to my spot and decided to wade across the river after we released the trout. I couldn’t get my cast quite as far as I’d like so I just got closer to where I wanted to cast. Unfortunately, I didn’t have the foresight to see the tree line in front of me. Despite, or maybe because of, my confidence growing, I ended up getting my line caught in the tree above me for about 15 to 20 minutes. I didn’t rush it or cut the line prematurely and got the $10-$15 fly unhooked from the branch.

Eventually, it started to get dark and we decided to call it without any other fish caught. We were exhausted from being in the sun all day, but I was satisfied with at least just learning how to cast. I asked Grayson at one point during the trip how long it took him to catch his first trout when he picked up fly fishing. He told me it was around his third trip he got one. So, I know Grayson is going to read this, but that just means I’m going to have to tag along for another two trips to find myself a rainbow trout.

I sometimes get complacent in my hobbies so it was refreshing to learn that there’s still worlds of culture and history that I’ve hardly seen, especially one so close to the rest of my current interests. I’m extremely grateful to have a friend like Grayson showing me something he’s so passionate about, and equally grateful to Robbie for documenting our trip.

Want to get early access to columns, unique newsletters and help keep The Sunrise News active? Then support us on Ko-Fi!

This article represents the opinions of its author. The views expressed here are not necessarily representative of The Sunrise News staff as a whole.