This article represents the opinions of its author. The views expressed here are not necessarily representative of The Sunrise News staff as a whole.

When I say the word “cave,” a person could pull from an endless amount of imagery from the world. From Minecraft caves to actual mine shafts, different stories of caving going wrong, to the Alabama state park Cathedral Caverns or the Alabama tourist attraction Majestic Caverns and more, people have a wide range of exposure to caves.

As fun as caves may seem in pop culture or in commercial settings that are well-lit with established paths, show caves can harm not just the cave environment, but surrounding ecosystems too if not managed correctly.

Wild caves, caves that do not host tours or are untouched, are one of the most conservation-heavy environments in the world. With biodiverse microbiomes that rival other untouched parts of the world, caves are prime areas to gain better scientific understanding of evolution, microbiology and antibiotics, geology and the overall history of our world.Known as the Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia or TAG region, TAG corner or just TAG, if you live in one of those three states you happen to be in one of the largest caving hotspots in the world. Not only are there thousands of caves in the area that these three states meet, but they’re some of the most impressive and largest systems you can find in the U.S. Some of the deepest caves in the country are located in TAG, with the deepest unobstructed pit in the U.S. located in north Georgia at a 586-foot drop.

Exploring these caves and seeing them firsthand can be a rewarding experience for any outdoor enthusiast, it’s important to know about the people and organizations who are dedicated to preserving these places and to understand best safety practices for yourself, other people and wildlife.

Among hundreds of organizations dedicated to caving in the Southeast are the Southeastern Cave Conservancy and the National Speleological Society.

The Southeastern Cave Conservancy, Inc. is a tremendous organization that focuses on saving caves through direct purchasing and managing of caves. They currently protect and manage more than 170 caves in seven different states with the help of volunteers from all over the Southeast. The SCCI also works to help educate people on the scientific and historic value of caves and on best practices to safely enjoy these underground wonders. At SaveYourCaves.org, the SCCI has compiled a variety of valuable information on clean caving and leave no trace principles, caving safety, geology, wildlife, history and how you can help save the caves. SCCI also provides permits for nearly all of their preserves. Before applying for a permit, and even though I studied Leave No Trace principles in college, I still familiarized myself with them and reviewed any of the local, county or state laws on caving.

While the SCCI helps preserve caves and provides permits in the Southeast, the National Speleological Society does so nationally. The NSS preserves and manages caves, but their main mission is much more focused on connecting cavers to other cavers, and newcomers to their local grotto chapters. With over 250 grotto chapters and over 8,000 members, the NSS provides a space for people to discover the world of caving. The NSS also happens to be headquartered in Huntsville.

If you don’t know what a grotto chapter is, it’s a local organization that hosts weekly or monthly meetings about caves. You can attend these meetings without being a member, but membership typically allows you more access, and more responsibility, to caving and other benefits. Find your local grotto here.

I’ve been a member of the Birmingham Grotto for about 6 months now, and a member of the NSS for about a month. Being a member of the Birmingham Grotto has allowed me to find more caving trips and meet more people who have helped me become a better, more cognizant and safe caver. Every trip I’ve been on with a grotto member, I’ve always felt like I’m with people who know what they’re doing and have left the trip learning something new.

On my most recent trip, however, none of us had been in the cave prior to the trip. I found myself sharing the lead with my former professor Dr. Turner, my friend Price and my brother Cole, all of whom have been in multiple caves before.

Equipped with a detailed map, we visited Lost Creek Cave located in Tennessee, about two and a half hours from Scottsboro, AL. The cave is managed by the state of Tennessee and is only open from May to August. We happened to go on the last day it’s open to the public, Aug. 31. The cave is located on a larger nature preserve that people do not need a permit to visit.

The reason for the cave’s closure between September and April is bat migration, more specifically because of the risk of White Nose Syndrome. WNS is a fungal infection that has nearly wiped out entire species of bats in North America. Prior to and after visiting caves you must ensure that all gear is decontaminated. It’s unknown how WNS began to transfer to bats as it was only found in parts of Europe and Asia before 2010, but it’s generally believed that it may have come from an infected bat that was introduced to the U.S. from outside of the country.

The cave at Lost Creek has one of the largest entrances I’ve ever seen. Featuring a waterfall to your back as you look in the mouth of the cavern, it remains wide open with tons of rockfall at your feet for about half a mile into the main passage. Eventually, after walking through the passage, we got to a rock shelf that, after arriving, gave us a few options.

The first option was to climb over the small shelf and keep going while the other options were the numerous side passages around us. After looking at our map that we obtained from the Nashville Grotto, we decided to keep moving forward.

Still passing numerous side passages, we eventually got to the end of the main passage where we were greeted with an underground waterfall. Looking at the map, we then realized why the area is called Lost Creek. Directly above us was the waterfall that we took a photo at across from the cave entrance. As the water filtered through the soil and rock, it must’ve carved its way through the limestone to help form the area of the cave we were now standing in.

Looking up, though, we also noticed some random lights — there were other cavers about 20 feet above us. We couldn’t hear them over the water rushing by, but we ended up trying to find out how they got up there for the next four hours.

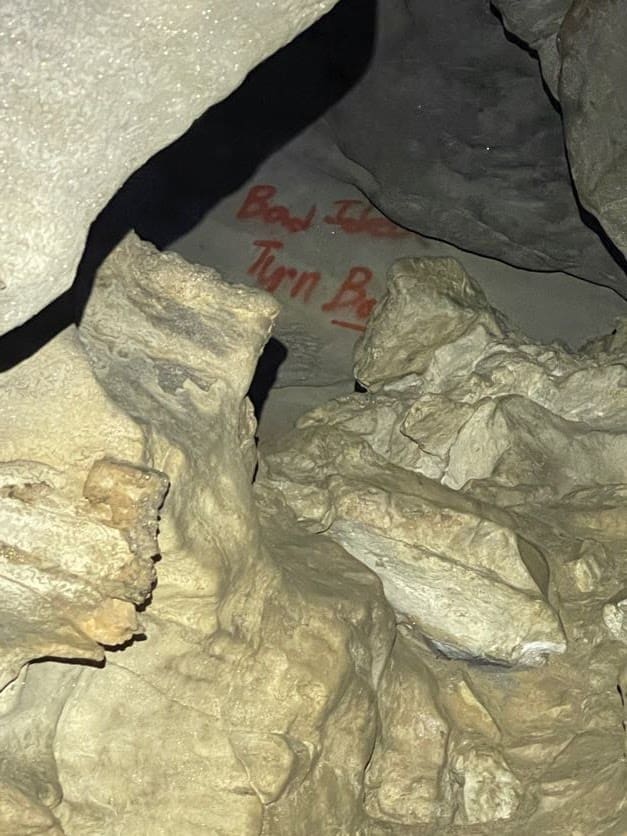

Through countless side passages while somehow never getting lost, mainly because of the excellent map we had, we kept finding gross amounts of trash and graffiti. It was possibly the most polluted cave I’ve ever been in. There was a lack of any major geological formations because of what we assumed and later saw for ourselves — spelunkers — or just bad cavers walking through.

Spelunkers — a caving community term, not the Merriam-Webster definition — are people who come to a cave without helmets, proper lighting, come with poor gear, no clue of where they may be going and leave trash in the cave or damage the fragile environments they’re trudging through. One of the first distinctions between a caver and a spelunker was in the NSS American Caving Accidents 1984 Issue.

We saw about 15 different people in separate groups who were walking through the cave in flip flops using their phone lights to try to make it to the waterfall. They put their own lives at an unnecessary risk, risked the lives of potential rescuers and possibly contributed to the damaged ecosystem in the cave.

All it takes is a single wrapper, spit-out gum or piece of food to cause significant change to the micro ecosystems in a cave. One piece of trash or outdoor material can quickly turn into a fungal paradise that then disrupts cave crickets, cave salamanders and the general food chain and ecosystem of a cave.

Some basic must-haves for going to a cave:

- Three sources of light

- Helmet

- Food and water

- First aid kit

- Proper clothing – No cotton as it holds moisture

- Stiff or rigid-soled shoes or boots

- A map

- Knee pads and elbow pads

Some best practices before and while you’re in a cave:

- Decontaminate your gear — decontamination steps can be found here

- Never cave alone

- Tell someone where you’re going and when you expect to be out of the cave

- Stay together

- Always have three points of contact when moving on uneven ground

- Never push yourself beyond your limits

- Leave nothing but footprints, take nothing but pictures and kill nothing but time

Additional best practices and information can be found here and here.

Despite the graffiti and poor practices noticeable in the cave, it was an incredible system. With large passageways to small tunnels, we had a thrilling experience exploring the cave. Most of the side passages connected back to each other as well, so it was an easy time exploring the main system. I even got to go through some of my favorite parts of a cave — squeezes, or passageways that require you to squeeze yourself through.

Every caver we met, who wasn’t a spelunker, was great to talk to and we even met the people we originally saw at the top of the waterfall. They were gracious enough to tell us how to get to the top, which we had walked by numerous times.

Overall, Lost Creek Cave is definitely a cave I’m going to return to, for the sole reason that we ended up comparing maps with another group and discovered there’s an entire separate system to explore. Before meeting that group, I had begun to crawl through the connection to the separate system with Price but we realized we were off our map and turned back.

If you’d like to visit a cave, I highly recommend checking out your nearest local NSS grotto. They are always a welcoming group of people and can help loan some basic caving gear and take you out on your first trip. I wouldn’t be as involved in caving as I am now if my professor hadn’t reached out to the Birmingham Grotto. I am forever grateful to be a part of the wonderous world that is caving. Save the caves, save the bats and connect to your local grotto.

Want to get early access to columns, unique newsletters and help keep The Sunrise News active? Then support us on Ko-Fi!

This article represents the opinions of its author. The views expressed here are not necessarily representative of The Sunrise News staff as a whole.